Back to Basics

By Andrew Avila

An old cardist once said, “think inside the box, everyone else is too busy trying to think outside of it.” At first read, this may seem like an attempt to stifle creativity since “out of the box” thinking is equated with creativity and is encouraged. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that “in the box” thinking can’t be creative. The quote could be interpreted as inhibiting. Indeed, if you know the quoted cardist, that interpretation may seem like the correct one, but another more useful (and more correct) interpretation is this: look inside the box for things that are neglected. Whatever the meaning of the quote, it leads into the focus of this article, which is to explore, exploit, and employ basic moves as an engine of creativity.

Regarding Basic Moves

Before continuing, the definition of “basic moves” (for the purposes of this article) will be clarified. Basic moves are easy and simple, and uniqueness is a plus.

Easiness is rather self-explanatory— the move shouldn’t be difficult to execute perfectly on a consistent basis. If the move is easy, creating off of it will also be easy since you (should) have some mastery over it or you should be able to quickly develop proficiency.

Simplicity means that the move doesn’t have multiple components or a multitude of movements. Compare Kryptonite and the Cobra Cut to a Revolution Cut and a Charlier. The latter are obviously the basic moves since they are composed of relatively fewer movements and mechanics than the former.

In these aspects, creating with basic moves is more beneficial than with complex ones. Basic moves are easy to perform, break down, and explore. However, more complex moves could be used for these purposes as well if they are broken down into components that you want to explore. For example, examining the midway packet fold in Nikolaj’s Underscore rather than the cut as a whole.

Finally, Uniqueness: this trait refers not only to the way a move looks, but (perhaps more importantly) the finger, hand, arm, etc. positions it presents relative to the cards. Said positions are points at which you can branch off of. More varied positions will lead to more different looking outcomes. That being said, it would behoove you to seek out unfamiliar basic moves as they will provide you with new positions and new stepping stones. The Encyclopedia of Playing Card Flourishes by Jerry Cestkowski is a great resource for such moves, but contemporary sources are also useful (and easier to get a hold of). Now that you know what to look for, the important thing is to find and recognize all of the positions and intricacies that a single basic move or movement contains.

Dissecting Basic Moves

As noted, it’s important to be innately familiar with a move in order to get something new out of it. What follows are some ways to accomplish this.

Perform the move. This may seem needlessly obvious, especially when you have a good grasp of the move, but it can still be helpful by doing it in different ways. Going through the motions of a move slowly (about as slowly as possible) will reveal the full range of motions it presents for the cards and for your fingers. Another way to explore through performing is stopping the move halfway (or at any other point).

While performing the move you should constantly be noting the relationship between the position of cards and fingers. During the course of a move these positions are in constant flux and each change presents an opportunity to branch off or do something different with the move. Some positions are more useful than others — a great example of this is the used and overused Z-grip, which spawned (is spawning) a myriad of very unique moves. All the while, some other position or grip (like those offered in Jerry Cestkowski’s Gearscrew Cut) has faded into obscurity or been overlooked. That being said, it’s worth exploring non-current, non-comfy, and otherwise non-used moves before discounting them; they may not be the next Z-grip, but they may still present something really interesting.

There are a variety of ways to branch off of positions: you can do weird things, useless things, things that might not work, explore the range of motions that are allowed, etc. Think about the different movements you can make at certain point in a move. Get into the habit of asking yourself what you can do differently, what might flow well, or even what might feel comfortable (#comfycardistry) at a certain point in the move. This may seem vague and unclear, but the examples below should help to clarify.

Apart from studying the positions afforded by a move, you should also look at the move as a whole. For example, you may not find many useful positions in a certain move, but it may fit into another move in the form of an opener, closer, or other movement.

Note: When creating off of another move, don’t think that you’re simply creating a variation of a move, but envision the move as a component or a kick start to something new. In other words, try to go beyond making a variation and do something different.

Basic Move Success Stories

Many of my moves are modifications of basic moves or they arose while messing around with one. Below are a few examples of this along with the thought process behind them.

Piano Cut

This mechanical looking flip-flop running cut has humble origins in the posterchild of basic moves: the Charlier Cut (it’s a great move to use for a creativity exercise). The process of deriving the Piano Cut from the Charlier resembled this:

•Do a Charlier halfway. At this point, all fingers are pretty free, but the thumb, index, and pinky are in a particularly good spot to act on the cards.

•Lever the bottom pack down with the index finger. This levering motion came to mind since the set-up to Prism has a near identical movement, albeit with the pack in the other orientation. Here the thumb pack can drop and the cut can close, which is how the move stayed for a while until the next step was realized.

•Drop the thumb pack and lever with the pinky. This mirroring motion led to the completion of the cut. From here, the index pack can be dropped and then (surprise) be recycled with the motions of a Charlier cut. Ad infinitum.

Untitled

A nameless packet sliding, hand tilting, feel good move, which all started with a Scissor Cut. It came up after noticing that Scissor Cuts don’t open or close with the packets linear, i.e. from a side view, the thumb-index pack is at a slight angle relative to the index-pinky pack. By retaining this angle throughout the close, the index finger can easily push the thumb-index pack along the face of the other. After this initial slide, the pack ended up mirrored in the same angle, allowing another slide (with the available fingers). From here, I looked for ways to keep this packet sliding pattern going until a suitable closing position was reached.

Six Pack

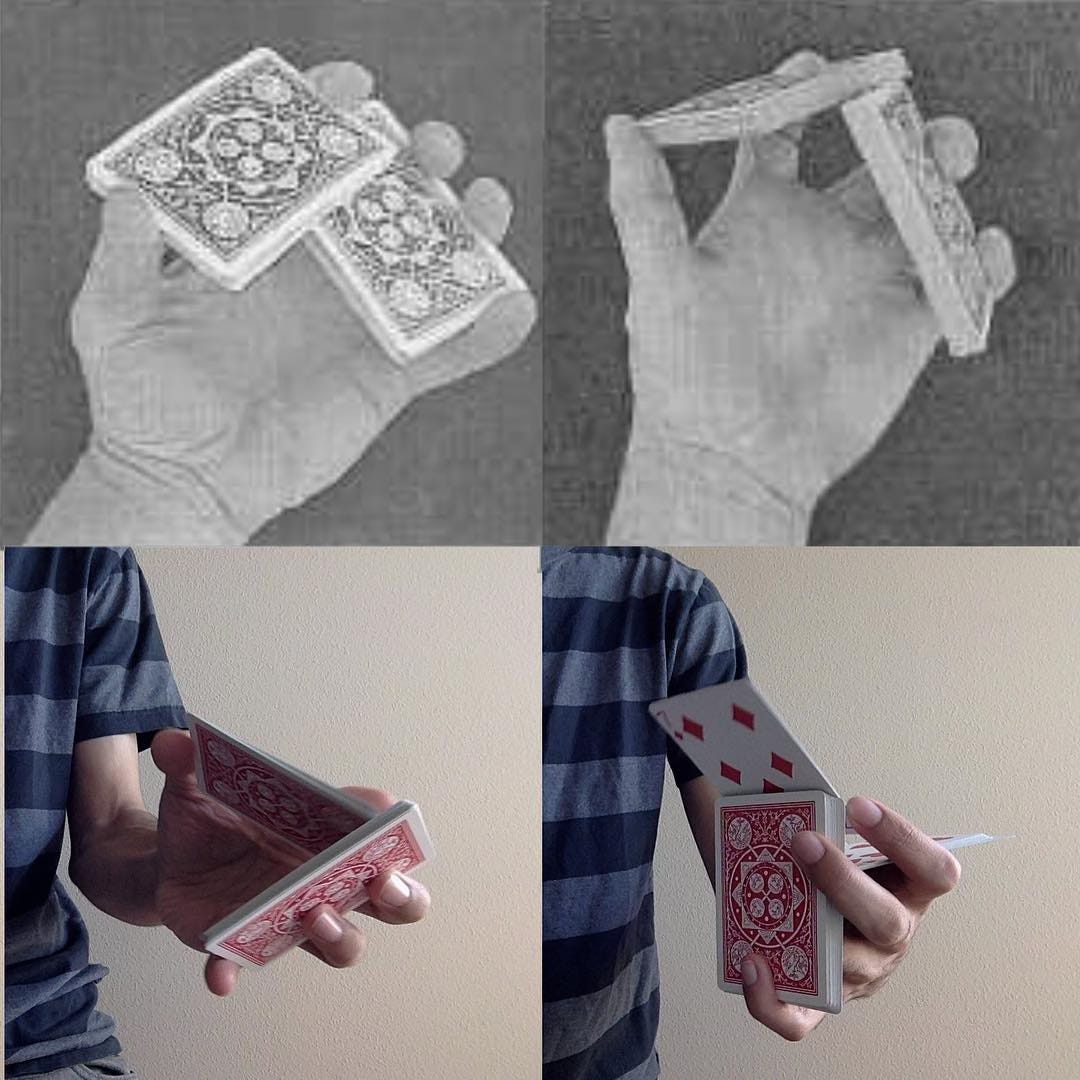

This efficient packet-multiplying display was discovered while tinkering with corner brackets (see fig. 1.0), but it lacked an opener.

fig. 1.0

(*editor’s note: image no longer available)

I needed a quick and simple method (maybe a basic method?) to align two packs next to each other at 90°. I was having trouble figuring out such an opener on my own. It’s a simple, but tricky problem to solve (feel free to explore ways to accomplish this, as another creativity exercise). I scrounged around the EOPCF for some answers and was reminded of Brian Tudor’s Revolution III when I came across Revolution cuts. Executing Revolution III halfway through aligns the packets and, with some help from the other hand, they end up ready to split.

Pincer Rotators

This packet reversing “cut” is the result of exploring the Pincer Grip Shuffle from the EOPCF. While in the exploration process I came across Jason Soll’s T3 cut, which has a very similar packet flipping mechanic. Combining this simple long-sided flip motion with the Pincer Grip Shuffle resulted in, for lack of a more creative name, Pincer Rotators.

So, Basically…

It seems fitting to end on another quote from another old cardist: “Trying to create a one-handed cut is not fucking easy.” There isn’t an obviously alternate way to interpret this one, nor should there be — I agree with it. Trying to create one-handed cuts or any kind of flourish is not easy. Besides just coming up with a move, you still have to iron out all the kinks, practice to proficiency, get feedback on it, repeat, and more. These are all crucial components to making a move, but their elaboration is another article. For now though, I hope this article has at least made the “come up with a move” part a less daunting task and inspired you to think inside the box of basic moves.

What did you think of the article? Do you have any such basic move success stories? Do you wish I listed more varied examples? Has this article helped you? Let me know in the comments!

About the author, Andrew Avila:

Andrew is a cardist residing in Portland, Oregon. Check out his download Assorted Works, where he teaches Six Pack and two other original creations. You can follow him @andrew.j.avila