I Have My Own Cardistry Style—Now What?

By David Lam

“Let’s say your favorite flourishers are Daren Yeow, Aviv Moraly, and Noel Heath. Take these three styles and combine them. You will later become a stylistic combination of those three individuals.” - Patrick Varnavas

This quote arguably shaped an entire generation of cardists, many of whom went on to become the faces of today’s cardistry community. Developing a personal style is a milestone worth celebrating—it marks the moment a cardist separates themself from their peers and establishes a distinct design language in the way they create and perform their own moves. But once that style is formed, what comes next? In this article, I want to explore how a cardist can continue to refine their personal style, the challenges that arise in doing so, and how we might rethink what it truly means to have a style in the community.

Further Exploring and Concentrating on Personal Style:

Once you’ve established a style, the next step is pretty straightforward: just keep making moves. That means finding new mechanics you’re drawn to and working them into your own material. If you’re creative enough, you might even end up creating new mechanics altogether, which naturally pushes your style even further.

For many cardists, this phase comes easily. At some point, you no longer need to emulate the people you like because you already have a design language of your own. From there, it’s mostly about refining—making things cleaner, more consistent, and more confident over time.

That said, it’s also completely fine to keep leaning on Patrick’s “three cardist” idea and gradually add more influences over time— that’s what most cardists do. That’s also why many older cardistry videos end with long lists of cardist credits. Pulling inspiration from different cardists doesn’t weaken your style if they genuinely inspire you. If anything, it helps you grow faster, broaden your perspective, and reinforce what makes your cardistry unique to you. That said, I want to take this idea a step further to suggest that developing a style isn’t strictly about understanding what you like—it’s also worth taking note of how others perceive your style.

Style as Seen By Others:

Not long ago, a close friend of mine, Hans Lankamp, and I played a simple game. We each listed four cardists that inspire us, then tried to guess each other’s lists. When it came time for Hans to guess mine, he named Lars Mayrand, Samuel Pratt, Nikolaj Honoré, and Patrick Varnavas.

Out of those four, he got one right.

My actual list was James Chesmore, Henrik Forberg, Tobias Levin, and Patrick Varnavas. Even though only one name overlapped, the differences were what I had found the most interesting. We tend to think of our influences as intentional choices, but others often see our cardistry more abstractly, drawing connections to styles we may not be consciously aware of.

It’s helpful to ask other people how they read your cardistry. Chances are, they’ll notice patterns and influences you’ve overlooked. In my case, it was especially meaningful because I already admired all of the cardists Hans mentioned. Seeing those connections from an outside perspective gave me new angles to explore and more reasons to go through their original work, all while continuing to develop my own style even further.

A Change of Approach in Cardistry:

At some point, I think every cardist reaches a moment where the way they’ve been doing cardistry becomes ineffective in giving the moves that they want. Whether it’s boredom, burnout, or simply outgrowing an old approach, you’re suddenly faced with a choice: keep doing things the same way, or—more controversially—move toward a different style altogether. This is one of the more challenging aspects of style to discuss. It doesn’t happen often, and when it does, the shift can be so drastic that it invites strong reactions. Both the cardist and the people watching them can feel like something has been lost, or that the cardist has stepped away from the identity they built within the community. I want to explore why changing styles can actually be a good thing and how moments like this can prompt us to reconsider what a cardist’s style truly represents.

An Assessment of Duy’s Cardistry Style:

A primary example of a cardist changing their style within the community is Duy Nguyen. Although he is now best known for intricate multicard isolations, which he dubbed card matrix, he was previously recognized for two-handed packet cuts with lots of corner spins. He was so proficient at creating corner spinning moves that a recurring joke at the time was his sarcastic remark that a move “didn’t have enough spin(s).” While his shift toward isolation routines was widely seen as refreshing back then, I personally found it disappointing, as it signaled that we likely wouldn’t see much more of his two-handed packet cuts—something that caused my interest in his cardistry to wane.

A Change In Perspective:

As of recently, in my own journey within cardistry, I’ve been experimenting with other genres such as fans, structures, and card twirls—this exploration proved to be eye-opening for me.

When I was exploring these different genres, I discovered that I could apply principles from them to my own two-handed cuts in ways I would not have considered otherwise. For instance, while relearning and creating my own card twirls, I realized that what my cardistry had been lacking was performance. Although my execution had always been technically solid, my moves often relied more on clean mechanics than on intentional presentation. Card twirling, however, does not allow for that kind of reliance; strong mechanics alone are not enough. To make the twirls engaging, I had to become a better performer.

This realization made me more conscious of how I present my moves overall, even in areas like packet cuts, where performance is not as problematic for me. As a result, my understanding of how to approach style has broadened significantly.

We’ve Never Changed Styles— Only Expanded Upon It:

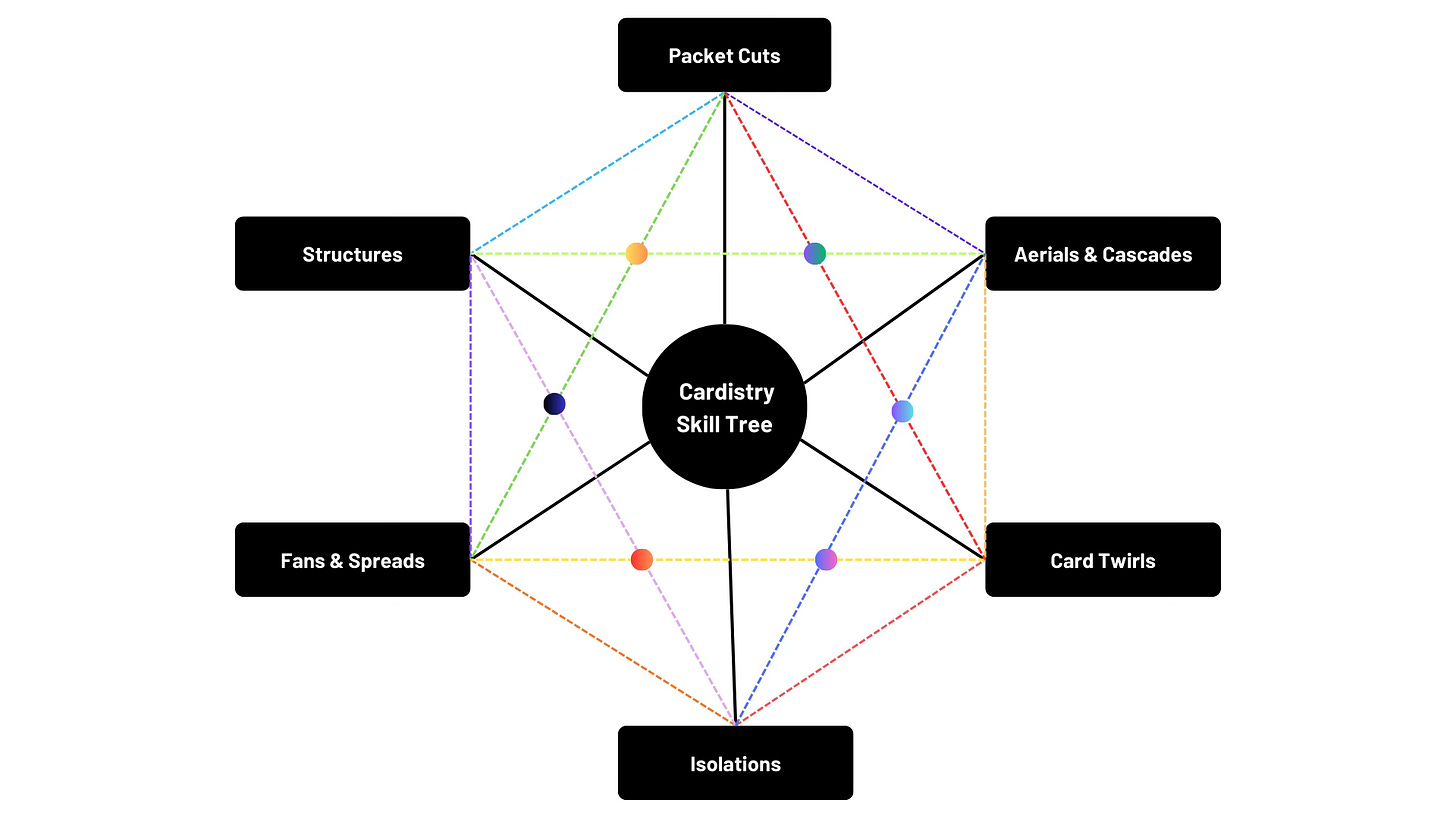

I want to propose the idea that the way we see style in the community is not this straight and narrow path that we see it as, but rather as a large skill tree, like the ones you’d see in Borderlands or Skyrim. Each genre of cardistry acts as its own branch, and as we unlock new skills, those branches start to affect one another. Even when we’re not aware of it, what we learn in one area ends up shaping how we approach everything else.

A Reassessment of Duy’s Cardistry Style:

To bring this back to Duy’s cardistry, part of why I initially found his transition from packet cutting to isolations so polarizing was due to how different those two genres appear on the surface. After reflecting on my own experience exploring other cardistry genres, I now recognize that my earlier analysis of Duy’s work was short-sighted. Rather than focusing primarily on the differences between his two-handed packet cuts and his isolation routines, I should have been paying closer attention to the underlying similarities that connect them within the larger context of his style.

When Duy’s packet cuts and isolations are viewed together, his style appears far more cohesive than I gave him credit for. His two-handed cuts are heavily defined by corner spins, and when seen through that lens, his isolation routines begin to make more sense—they function, in many ways, as an extension of the same corner spining ideas, simply expressed through isolations. To put it simply, Duy’s thinking shifted from “this packet cut needs more spin(s)” to “this isolation needs more spin(s),” a transition that remains fully consistent with his personal style.

In addition, I’d argue that Duy’s deep understanding of corner spins from packet cuts directly informs the way his isolations function. That influence carries over in a way that makes his isolation work distinctly his own, rather than a departure from his earlier style.

A Further Explanation of Patrick’s Quote:

When we first begin developing our own style in cardistry, it’s easy to fall into the misconception that we have to limit ourselves to only a few specific genres. As a beginner, this makes sense, as this was an easier way to establish a clear design language quickly, which allows other cardists to recognize our work. However, once that style is established, it can begin to feel limiting to what we can do.

When you reexamine Patrick’s quote, he mentions Daren Yeow and Noel Heath—two cardists who sit on opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of both their approach to cardistry and the genres they specialize in—yet he suggests that if you appreciate both of their styles, you should feel free to combine them. This shows that your favorite cardists or genre of interest do not need to be adjacent or closely related for your style to feel cohesive.

While it may initially feel jarring to include an isolation routine alongside a moveset that focuses primarily on packet cuts, it is completely valid as long as those choices align with your personal taste. As long as you bring your own unique perspective to these different aspects of cardistry, your style will remain cohesive in spite of these contrasting interests.

Jack’s Genre Change Assessment:

One notable example of a cardist shifting genres successfully is Jack Trathen, co-founder of Cardistry Core. When I asked people to name a cardist who has significantly changed their style, it’s surprising that his name rarely comes up. In 2025, his work moved from complex two-handed packet cuts toward more structure-based moves. While a few people in my close circle noticed this shift, I think there’s a clear reason why it goes unnoticed.

When comparing Jack to other structure-focused cardists, such as Andrew Avila and Trevor Aguilar, it becomes obvious that his background in two-handed packet cuts still heavily influences his structure work. Structure moves often prioritize a large visual payoff, which can lead to openers and closers feeling less important. Jack, however, treats structure moves more like composed routines than a direct path to a climax.

His structure moves carry the same sense of rhythm and energy found in his packet cuts. From the explosive pacing of Eurostep to the subtle pinky flick at the end of Holy Grail, these small, hyper-stylized actions are what make his structure moves stand out—especially when compared to cardists who specialize in the genre.

This is also why Jack’s shift in style doesn’t feel as drastic as it actually is. Rather than abandoning his earlier approach, he presents structure cuts with the pacing, framing, and intent of a two-handed packet cut. As a result, his work feels consistent with his overall design language, even as the genre itself changes.

Pushing Towards An All-Rounder Mindset:

In the grand scheme of this article, I could have reframed this discussion to encourage cardists to adopt a more generalist approach to cardistry. However, many of the ideas surrounding style naturally overlap with that concept already. Becoming more of a generalist is not simply about collecting moves from different genres for the sake of diversifying one’s move portfolio; it is about understanding how and why those genres work, as well as seeing if those respective genres would fit within your own style.

Even if you don’t plan on including these genres in your overall moveset, just learning about performance through card twirling, shape construction through structure moves, or the physical properties of a deck through fans can each offer a broader perspective on how to expand your own cardistry style.

Conclusion:

Continuing the discovery of one’s style does not mean abandoning what you already like or what you are known for. It can mean refining that focus just as much as it can mean stepping outside of it.

By either doubling down on what resonates or intentionally exploring unfamiliar genres, cardists open themselves up to deeper connections between skills that initially seem unrelated.

In doing so, style becomes less about staying within fixed boundaries and more about understanding how those boundaries can expand—allowing your own style to evolve without feeling like your identity will get lost.

So if you find yourself wanting to explore isolations, fans, etc, go for it. Who knows—you might weave these principles into your moves, make them part of your own repertoire, or even switch genres entirely. I guarantee that you will learn something new along the way, which will further enrich your personal style.

About the author, David Lam:

Hi, my name is David Lam and I am a cardist from New Jersey. Catch me jamming on any of the current cardistry discords sometimes. Otherwise, my IG is @mercq. Thank you for reading.

Liked what you read? Tell us why in the comments below!